Why we need an intergenerational approach to making fashion more sustainable

Solving the climate crisis requires a collective effort. How can we collaborate across generations to make fashion more sustainable?

What younger generations can learn from older generations

Knowledge and experience in the fashion industry

Sewing and mending clothes to make them last

The importance of holding onto clothes for longer

Technical and specialised skills from formal fashion education

What older generations can learn from younger generations

Their passion and urgency when it comes to the climate crisis

How to use online resale markets to give old clothes a new life

How to educate and inspire using digital activism

The power of technological innovation in new fields such as bio-design

The fashion industry is infamous for the way it fetishises youth. This desire to constantly be searching for the next best thing is the same desire that fuels fast fashion. A more collaborative approach that spans generations is necessary in the face of the climate crisis. Fashion has always involved intergenerational collaboration to some extent, whether that’s between designer and muse, student and tutor, or patron and protégé. However, ageist views can still hold the industry back from realising the full potential of intergenerational design. Older generations are sometimes considered out of touch or unwilling to change while younger generations are not always listened to or taken seriously because of their perceived inexperience.

27-year-old fashion designer Matthew Needham is known for upcycling deadstock and fly-tipped waste. He works closely with Fashion Revolution and with environmental activist Orsola de Castro, 54, in particular. The duo exemplifies the power of intergenerational collaboration in fashion, such as coming together to host upcycling event DiscoMAKE which encourages people to think about their fashion consumption and upcycle or remake clothing into something they would want to keep forever. Matthew describes meeting Orsola as “one of the best things that’s ever happened to me. She has been an advocate for upcycling for 25 years and was turning heads with her moth-eaten jumpers before the word ‘sustainable’ was even whispered. She has taught me so much about the industry both past and present.”

“Meeting Orsola is one of the best things that’s ever happened to me. She has been an advocate for upcycling for 25 years and was turning heads with her moth-eaten jumpers before the word ‘sustainable’ was even whispered. She has taught me so much about the industry both past and present.”

Images from left to right: Matthew Needham at DiscoMAKE. Matthew Needham, Insider-Outsider, Dutch Design Week 2021. Orsola de Castro [left] with Joss Whipple for Other Day Podcast Episode 18.

Make do and mend

However, exchanging attitudes towards sustainability often starts much earlier than fashion school and comes from people with no direct involvement in the industry. For many, their first introduction to sustainable fashion doesn’t involve the word ‘sustainable’ at all. Making clothing last is simply a financial necessity and an attitude ingrained from previous generations who grew up in a time of lack, pre-fast fashion. Clothing was purchased with the knowledge that it would be mended or passed down to other family members. Everyone knew how to sew and mend clothes so they wouldn’t have to be thrown away, a skill that was passed down from generation to generation. In some families, it still is but it is not as widely taught as in the past. Passing down knowledge about how to mend clothes is one way for older generations to help younger generations be more sustainable.

“First year of uni, I actually got in trouble for cutting up my toiles to re-use the fabric for the next ones.”

When 21-year-old fashion student Riac Oseph started his BA, he struggled to come to terms with the amount of waste produced on the course. “First year of uni, I actually got in trouble for cutting up my toiles to re-use the fabric for the next ones,” he says. It’s an approach to fashion that was cultivated by his upbringing. “In my family and most Indian families that I know, we never throw away clothes,” he continues. “We pass all our clothes down to our younger siblings until they outgrow them, then they’re passed on to cousins or friends and it continues until the clothes are unwearable. When they get to that point, we use them as rags and dusting cloths around the house. These are fast fashion clothes that are generally deemed ‘unsustainable’ but we stretched them way beyond their life cycle.”

For footwear consultant Susannah Davda this “less is more” approach is also something she learnt from her family. The 39-year-old is now passing down to her son what her father taught her about making things last. “My dad frequently told me and my three siblings to “make it last” when we were growing up,” she says. “This simple message of valuing what we have, repairing it when it breaks and buying quality in the first place is one that can be shared with our children and parents alike. When my son breaks a toy, I will explain why it is important to look after our things and show him how I fix it or explain what will happen to it now it is beyond repair.”

How can fashion education encourage intergenerational collaboration?

Outside of the family, the earliest exchange of intergenerational knowledge usually takes place in an educational setting. Today all fashion courses mention sustainability but, is that enough. Susannah believes that discussions about sustainable consumption should start at a much younger age. “I think it is imperative to educate the younger generation, ideally in a school setting,” she says. “They need to know the questions to ask about the products they are buying, be able to spot greenwashing and learn to value what they buy.”

19-year-old student and activist Gaia Ratazzi shares educational resources about sustainable fashion with her 55,000 Instagram followers. She suggests that digital activism can be a more inclusive and accessible mode of sharing information than traditional fashion education. “Formal education can definitely play a role,” she says, “but a lot of people can’t access it and it’s also quite biased as it often only portrays a western point of view without acknowledging other culture’s contributions towards sustainability.”

Gaia also shares information about the rise of resale and how to sell your clothes online. Younger generations have made second-hand clothing cool, using apps like Depop and Vestiaire. Many Gen Z are more likely to proudly proclaim that their clothes are second-hand and be a little ashamed about their fast fashion purchases. Gaia says that young people who are able to harness the power of the internet “can help drive sustainable action by bringing people together through digital activism and help find information and news that can enhance our knowledge of the topic.”

Breaking down the barriers of ageism

Ageism in fashion goes both ways. The ideas of interns and students are often brushed aside or not taken seriously because they lack experience. However, ageism against older generations, and older women in particular, has a larger knock-on effect. It’s predicted that ageism could cost the fashion industry £11 billion in the next 20 years, according to research published last year by the International Longevity Centre which found that while older consumers have the most spending power, institutional ageism makes older women feel like “frumps.”

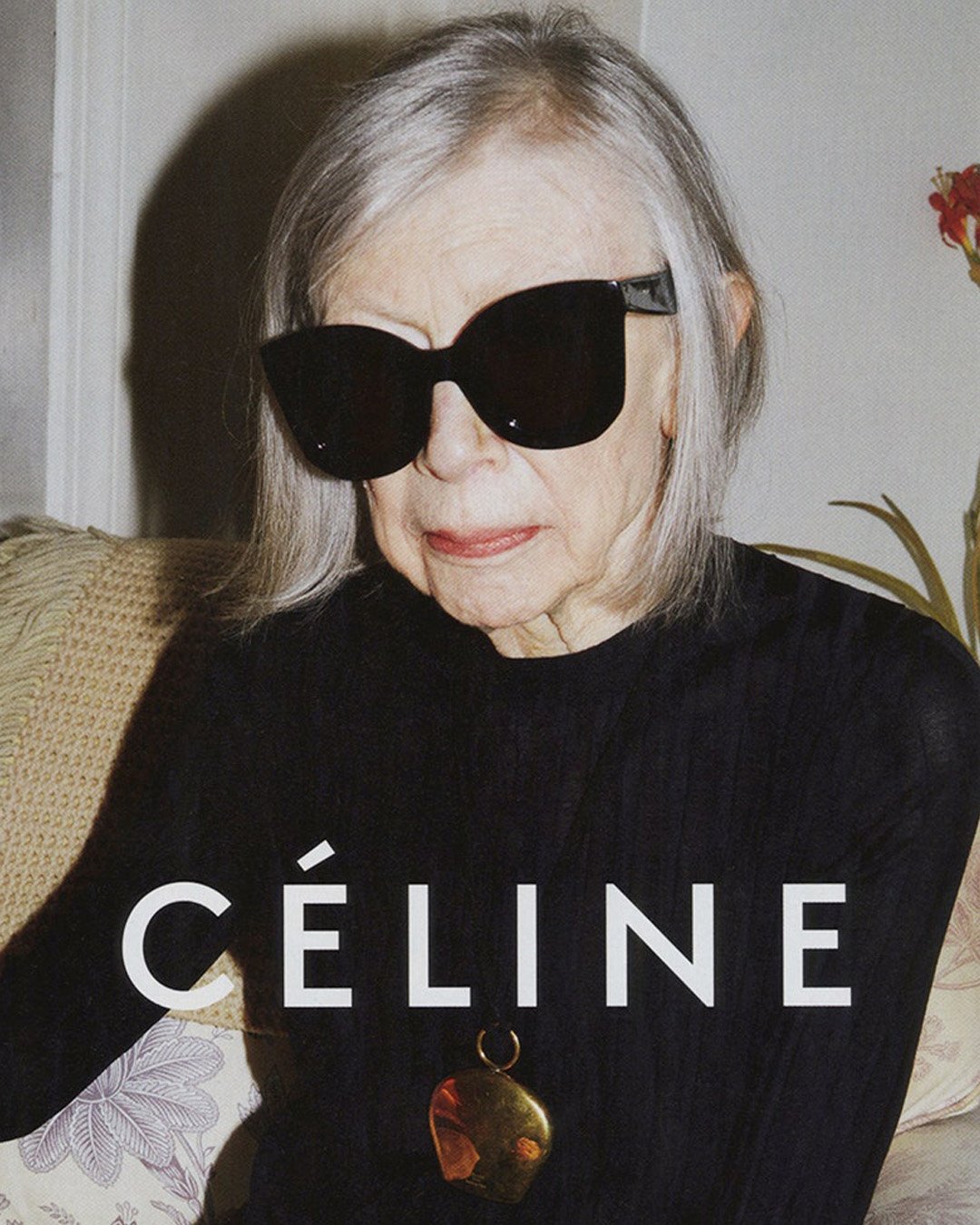

Some brands have started casting older models in runway shows and campaigns. Perhaps one of fashion’s most high-profile intergenerational collaborations in recent years was when Phoebe Philo, then 42, cast writer Joan Didion, then 80, in a Celine campaign in 2015. But this is still far from the norm. Fashion’s obsession with youth can leave older consumers feeling disengaged and like their voices, viewpoints and opinions don’t matter even though that is far from the case, especially when it comes to taking a collaborative approach to sustainability. Brands have become adept at marketing a “less is more” sensibility to eco-conscious millennials and Gen Z, but for older generations, this approach is not new. They have already been investing in slow fashion for years.

Joan Didion photographed by Juergen Teller for Celine Campaign Spring Summer 2015, New York 2014.

“Age doesn’t matter in a newfound area like bio-fabrication because we’re all learning everything right now. It’s all been developed in recent years. A student in their 20s might know even more than someone who’s been in fashion for 20 years.”

Respecting and listening to all viewpoints is crucial. Younger people may feel their ideas are easily dismissed, but in new fields, such as bio-textiles, everyone is learning together. Ana-Maria Dragieva, 22, who studies biomaterials at London College of Fashion says, “Age doesn’t matter in a newfound area like bio-fabrication because we’re all learning everything right now. It’s all been developed in recent years. A student in their 20s might know even more than someone who’s been in fashion for 20 years.”

Intergenerational design

For some brands, intergenerational collaboration is key to their vision. Paris-based sustainable brand Good Morning Keith, who source deadstock materials from couture houses, is a collaboration between 27-year-old grandson Julien Aussel and his 82-year-old grandmother Paulette Amar. Aesthetically inspired by the 60s, Paulette brings her lived memories of the era and Julien uses his marketing knowledge to promote the brand on Instagram. “I’ve always loved clothes and made a lot for me and my family,” says Paulette. “I share the same passion for clothes, music and the 60s with Julien so working together made sense. In the 60s people were starting to become more environmentally conscious. Some people were talking about sustainability when I was young, but it wasn’t trendy. Today it feels like everybody is talking about it.”

“Working with her came naturally and she knows how to sew,” says Julien of collaborating with his grandmother. “The way that fast fashion labels produce makes me sick because I can see it’s nearly impossible to produce a collection in a week or produce a pair of £20 jeans without using any chemical products and underpaying your employees. I couldn’t imagine starting a project and hurting people with my dreams.”

CEO Sarah, 40, and Communications Manager Jess Rigg, 20, work together at organic underwear brand Y.O.U. “We’re a small team with varying ages so everyone has a different outlook,” says Jess. “Collaboration is so important in general but especially in the sustainability movement. Younger generations can learn so much from people who have come before us and who have been campaigning on this for years.” Sarah was inspired by seeing her parents campaigning when she was younger and says she “took some of that activist spirit with me through the years.”

While Jess acknowledges the importance of intergenerational collaboration, she suggests that the largest divide comes not from different generations but from wealth disparity. “Richer people are contributing to the climate crisis at a much higher rate,” she says, “especially when you consider the global north/south divide.” Most people’s first interaction with a “less is more” mindset comes from an economic necessity rather than a desire to be more sustainable. After all, it’s not the poorest groups in society who are keeping fast fashion alive.

In summary

For fashion to become more sustainable we need to combine the old (slow fashion, mending clothes, hand-me-downs) with the new (bio-textiles, digital activism, innovation.) A “less is more” approach is already familiar to older generations and young people can learn a lot from their viewpoints and skills. Fashion education is a great place to learn more about sustainability, especially for aspiring designers who wish to take a specialised path, but it is not the only way or even the main way to exchange knowledge between generations. Brands that are moving past ageism and cultivating a truly intergenerational environment where everyone’s ideas are listened to will be able to harness the benefits of both experience and innovation when it comes to sustainability and beyond.

Header image: Ageless Fashion via whowhatwear.co.uk